|

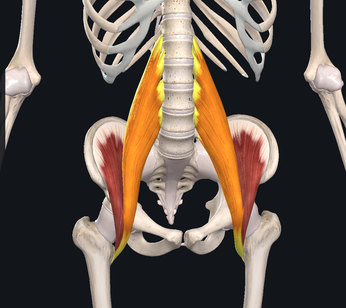

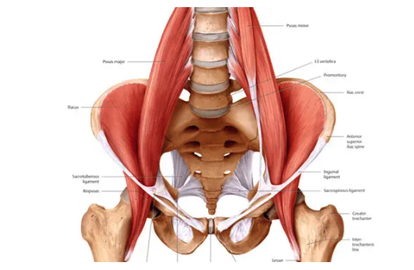

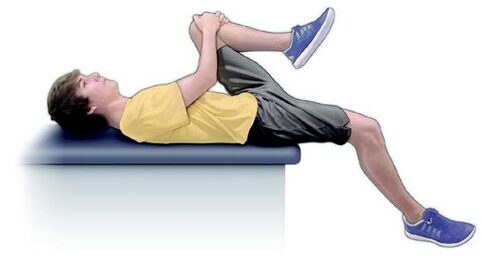

We've spent the last few Muscle Mondays focusing on the upper body, particularly about posture and how it affects our muscles and joints. Let's take a moment and look at one of the integral team members of our "core" and a common culprit for low back-related issues. Allow me to introduce to you, the Psoas Major (silent "P"). While there are many unique features about this muscle, perhaps the most significant is the number of joints that it crosses. This muscle originates at the transverse processes of T12-L4, crossing 5 spinal segments before going distally and inserting into the lesser trochanter of the femur. Because it crosses so many joints, it is responsible for 3 main movements including: Lumbar flexion, ipsilateral side-bend and hip flexion. Because of its attachment on the inside of the thigh, it also will slightly externally rotate the femur as well. Trunk/Lumbar flexion Trunk/Lumbar Sidebend Hip Flexion The primary job of the Psoas is to flex the hip. It joins together with the iliacus muscle to form the iliopsoas tendon. One of the main issues that people commonly face, particularly those who have a more sedentary lifestyle or job that requires several hours of sitting, is that the muscle will gradually adapt and shorten over time. Why this is an issue, is that this can result on increased stress on the lower back when you try and stand up tall/straight due to the tightness of the muscle which naturally would pull you into more trunk and hip flexion. In order to compensate, you would extend (or arch) your back more to allow you to get into the full upright position. Other common issues related to the psoas major are hip flexor tendinitis and/or "snapping hip syndrome" (the two are NOT synonymous). Hip flexor tendinitis describes an acute inflammation of the iliopsoas tendon and commonly painful with active contraction of the hip flexors. On the other hand, snapping hip syndrome is a condition in which a person may experience or hear a popping/snapping sensation in the front of their hip when they flex their hip, but may or may not be painful when the sensation occurs. Snapping hip syndrome typically indicates that there is friction on the tendon (which causes the "snap"). It could potentially lead to tendinitis and scar tissue formation of the iliopsoas tendon. Both of these conditions are commonly found in dancers, bikers, soccer players and runners. One quick and simple way to check to see if you have tight hip flexors is to perform a Thomas Test. While this is most commonly performed by a healthcare professional in the clinic, it is simple to do and can offer helpful insight to help you fine tune your body. To perform, you lay down on a bed while hugging one knee towards your chest. The other leg (the one you are testing) would drop down towards to floor. If you feel your back start to arch up, or if your femur (thigh) does not reach parallel to the floor, it would suggest that you have tightness/stiffness of your hip flexors. Do not, however, perform this if you are unsteady (in other words, don't fall off the bed), or if you already have pain in the area. Please make sure to seek advice from a medical professional for more detailed assessment. One very simple and easy place to start would be to start a simple stretching and strengthening regimen. Follow along in the video below to learn one of my all-time favorite stretches that I personally do on a daily basis. Of course, this is all about balance. Not only is stretching largely advisable to help maintain good habits, but it is also important to strengthen the appropriate muscles as well. In this particular case, it is important to focus on the glutes (Max, Med). Make sure that if you sit for work or school, that you get up and stretch a couple of minutes or walk around every hour. As always, check in with your friendly neighborhood physical therapist for specific guidance and tips to help you keep your body in prime working condition.

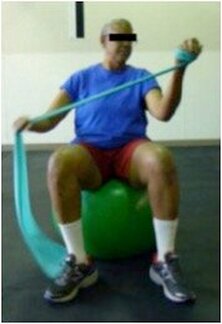

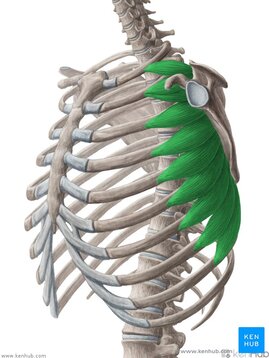

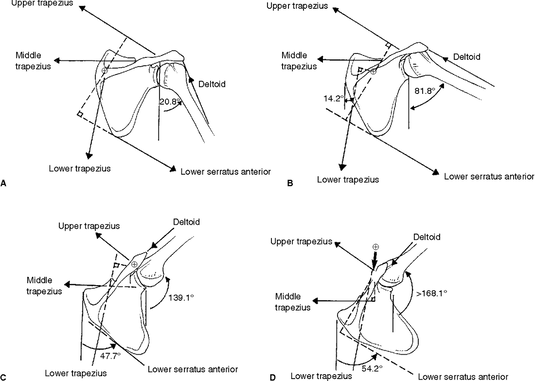

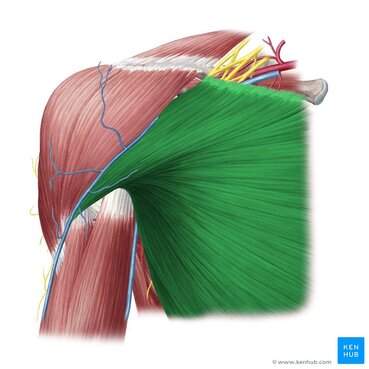

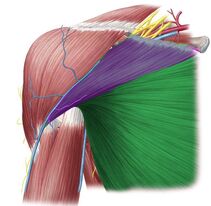

Until next time, Opus Fam! One of my favorite body parts to treat is the shoulder. Maybe because I relate to patients who have shoulder pain because of my own history, but maybe because it's like a puzzle with a ton of moving parts. The rockstar of the shoulder, of course, is the rotator cuff. But let's take a moment and talk about the often-times forgotten unsung hero - the Serratus Anterior. With 17 muscles attaching to the scapula (shoulder blade), it's really easy to get lost in the complexity of it. Everything has to work "just-so". When we look at how the shoulder moves as we raise our arms either out in front or to the side, our shoulder blades move as well. This scapular motion allows us to reach above our heads without pinching or putting more compression on the rotator cuff tendon. Source: Complete Anatomy So without further ado.... let's introduce the star of the show - the Serratus Anterior. This amazing, broad muscle attaches on the underside of the shoulder blade (sandwiched between the ribs and the scapula) and inserts into the first 8 (of 12) ribs. It gets its name from the Latin root "serrare" - meaning "to saw" based on its jagged appearanace on the ribcage. When it contracts, it works to rotate the shoulder blade upwards and wrap around your torso as seen in the video above. If the shoulder blade didn't go through this rotation, it would actually contribute to pinching or impingement of the rotator cuff tendons in the subacromial space. The second function of the Serratus Anterior is that it keeps the shoulder blade close to the trunk. Without it, it would peel away, causing the shoulder blade to stick out or become more visibly prominent. Because your shoulder blade is not anchored by any ligaments except at the humerus and clavicle, it relies on the synchronization and stabilization through muscle co-contractions. People who have significant weakness in their serratus anterior will often exhibit more prominent, pronounced borders of their shoulder blades through movements of their shoulder girdle as seen in the video below. (hint: focus on the right side) While there are many exercises that are useful to help strengthen this all-important muscle, here is a quick and simple one that I like to give violinists/violists to help build the endurance of their shoulders to help them be able to hold their instruments up for longer periods of time. Remember - it is highly uncommon for a single muscle to work by itself without having other supporting players involved. The shoulder is no exception. Make sure that you take time to put in the effort to create good balance throughout your body, but particularly in the shoulder. Having a good, solid foundation at the shoulder blade will help you be able to move more freely and improve the overall dexterity in your wrist and fingers.

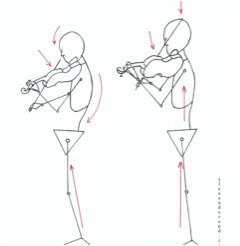

That's it for this week! Til next time.... Stay happy and healthy! Originally posted on www.corpsonore.com July 15, 2020 People often ask me why I decided to become a physical therapist. After all, most of my peers in my PT school cohort were either biology or kinesiology majors, and definitely NOT piano performance majors like me. My answer often begins with a stifled deep breath as I quickly decide whether to give the long or abridged version of my story. The short version goes something like: “I decided to take the scenic route and was a pianist and violinist before I got injured and decided to pursue physical therapy to help injured musicians.” Truth be told, physical therapy failed me. As an injured musician, I essentially tried every treatment under the sun - from months of acupuncture to several bouts of physical therapy treatments. My music teachers/professors could only offer me technique and postural corrections that seemed to make my pain worse. My PT gave me exercises that didn’t make any improvements to my symptoms. In the midst of my frustration, I realized that the error was not necessarily due to the people who were trying to help me, but that there was a huge void between the two disciplines that needed to be bridged. As a PT, I’ve spent the last decade of my career working to develop treatment strategies for musicians of all types and genres. The realm of performing arts medicine has grown and evolved as more research has examined the things that affect us and make us tick. More musicians have a deeper understanding of anatomy, physiology and movement than I ever did as a young artist. Movement-based education such as Feldenkreis and Alexander Technique are more widely-recognized and accepted, musician health curriculum is now required in NASM accredited schools. Despite this, most of the research has observed significantly high rates of injuries among musicians compared to the average US workforce (54%) [1] without any significant decrease in injury rates since the first major prevalence study by Fishbein M, et al. in 19882 (76%) In fact, recent studies have actually found higher rates of injury (up to 93%) as of the most recent systematic review in 2016 [2]. The question is: Why?  Image Credit: www.alexandarand.com Image Credit: www.alexandarand.com The fact is that most instrumentalists spend many hours in awkward positions while playing their instrument without task-specific training to supplement their playing. Professional athletes spend hours training and strengthening for their specific sport. You would be hard pressed to find a pro golfer training the same way as a defensive lineman. Musicians should, and need to, look to train their bodies to withstand the physical demand required to play. Only a few quality studies have looked at exercise training in musicians [4], much less with instrument-specific training. In both the music and performing arts medicine worlds, instrumentalists are typically divided into groups by families of instruments. Instead, we should really be looking more towards the postures used to play an instrument in order to help determine the best approaches towards “prehab” and “rehab”. When we talk about injury prevention from a musculoskeletal perspective, it is never just about strength. In order to perform at our best, we must always be striving to find the goldilox balance between the appropriate strength, flexibility, and nerve mobility (not to mention psychology, nutrition, etc., but that’s for another discussion and other experts to also weigh in on). Each instrument has its own physical demands associated with playing, and vary greatly from instruments to genres. In fact, it’s one of the biggest challenges as a PT who specializes in working with all types of musicians. For example, violinists, violists and flutists are presented with unique challenges compared to their other musician-counterparts because their playing positions force them to perform at more extreme ranges of their shoulders/wrists. In fact, they present with relatively high injury rates when compared to other instrumentalists [5], [6]. For these artists, almost the full range of shoulder external rotation (90 degrees) in order to effectively hold the instrument (left shoulder for violinists and right shoulder for flutists). If an artist doesn’t have the flexibility (either due to muscle tightness or their own anatomy), the body will cheat and find ways to still accomplish the task of playing. Additionally, the muscles that help support these joints should also be trained in these ranges. Just because you don’t have full range of motion, does not necessarily mean that you should not and cannot play. This is why playing is so individualized and not one-size-fits-all. There has been a lot of impressive content on musician wellness emerging these days that I believe is beneficial for ALL musicians, regardless of the instruments played. Particularly when musicians grapple with the common debate whether strength training is beneficial or detrimental to their ability to play. Will strengthening cause me to lose my dexterity? Will putting weight on my hands while holding a plank or performing push ups hurt me? While the short answer is no, just know that there are many many ways to go about strengthening and are not limited to a core set of exercises. If you are someone who either is suffering from an injury, or just looking to learn how to take care of yourself to prevent injuries, these are the 5 main suggestions I have regardless of where you are in your journey: LEARN ABOUT YOUR BODY AND HOW IT WORKS I do not believe that every musician should go through an entire anatomy course like I did, complete with cadaver dissections and mock surgeries. However, I strongly believe that ALL musicians should have a basic understanding of how muscles, nerves and joints work, and what muscles are instrumental to help them not only play their instruments, but also perform their daily tasks. BECOME FAMILIAR WITH BASIC MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY Nothing is scarier than the unknown, particularly injuries that you don’t know how to fix. The terms “carpal tunnel”, “tendonitis”, “overuse injury” are thrown around in our everyday vernacular, but oftentimes they are used incorrectly. If you understand what injuries are and what tissues are affected, you will be better equipped to take the first steps to try and modify your situation before going to see a medical professional. Don’t wait too long to ask for help. If you must see a medical professional like me, learn how to talk about your symptoms and their patterns (does your pain hurt after a long period of time? Certain positions? Repertoire change? etc.). We love to be detectives and help you overcome your obstacles, but if you aren’t able to give us a ton of information, it makes it more challenging to figure out. YOU HAVE TO CRAWL BEFORE YOU CAN RUN A common mistake I see instrumentalists and general patients alike make, is that they often rush into exercise programs without first assessing their baseline levels. You must have a strong foundation of strength and body control before you attempt to do more challenging movements. Otherwise, you’re just reinforcing or building bad habits, which as musicians, you know takes much longer to undo. TRAIN AS YOU PLAY  As I alluded to earlier in my discussion, musicians also need to train their bodies in the positions they use to play. That involves identifying the correct muscle groups to help support/stabilize you and your instrument and strengthening in the correct manner. A LARGE portion of my work as a PT is to first make sure that your body is flexible/strong enough to work in the positions needed to play an instrument. Second, strengthening muscles in the correct manner - for violinists, that may mean isometric strengthening for the left shoulder, while concentric/eccentric strengthening for the left shoulder/elbow. Flutists would vary, and primarily focus on isometric strengthening for both arms. Every instrument has different muscular demands and should be respected. Last, for “sport-performance” training, challenge your body beyond the normal confines of playing while performing the functional exercises. The more versatile you are within this skillset, the more your body will be able to adapt in changing environments. Last but not least.... BE YOUR OWN ADVOCATE: FIND A HEALTHCARE PROFESSIONAL WHO WILL TAKE THE TIME TO LISTEN. While I hope none of you end up in the situation that involves you having to go see a healthcare professional, make sure you take the time to find someone that will listen to YOUR story and put in the effort to work within your context. A good practitioner should work with you as part of a team, with you at the helm and in full control. This is regardless if they specialize in working with artists or not. Also know that you don’t have to have a problem in order to reach out for help. Talk to us about your questions and we are usually happy to equip you with the resources you need to become more empowered to take care of yourself and be proactive in your health journey. The musician health movement has come a long way, but there is much more work to be done. I would encourage all musicians to invest the time to learn about how to care for yourselves and don’t be afraid to talk to each other about your challenges. Your body is your main instrument. Your musical instrument is merely a tool for you to create your art. If you are an artist, know that there are healthcare practitioners, like me, who specialize in working with performers and are dedicated to helping artists stay healthy and injury-free. And just like artists, we do it not because it’s just a job, but because it’s our passion. Citations:

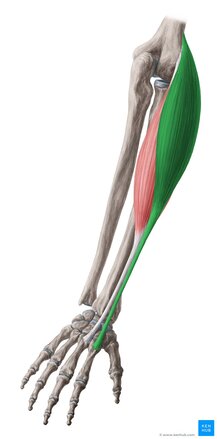

With summer in full force, we're all looking for ways to get out, stay active and get some much-needed Vitamin D. As we venture outdoors and get back into various types of physical activities, it's always important to do it gradually. Weekend warrior-ing is totally fine and acceptable, as long as you are a smart and wise warrior. One of the more common injuries people experience in the upper portion of their bodies is the infamous "tennis elbow", AKA Lateral Epicondylitis. "Tennis Elbow" is a bit of a misnomer, because only 10% of the patients who suffer this injury actually attribute the pain to playing this sport (source). This week, we introduce the muscles that are affected in this condition - Extensor Carpi Radialis Longus (green) and Brevis (red). A lot of times, you hear the term "tendinitis" thrown around. Tendinitis merely describes "inflammation of the tendon" but doesn't necessarily tell you which muscle tissues are hot and angry at you. Where the symptoms are, tells you a lot about which muscles need the most help. Lateral epicondylitis is one of the most common overuse injuries in the upper body. It describes tendinitis of the common extensor tendon which attaches on the outside (lateral) of your elbow. The Extensor Carpi Radialis Longus (ECRL) and Brevis (ECRB) both share this common extensor tendon, but attach at different points in the hand. ECRB attaches on the middle/long finger and the ECRL attaches on the index finger. Both work to extend the wrist and their corresponding fingers. Of the two, the muscle that is most commonly affected in lateral epicondylitis is the ECRB. Both wrist extensors are responsible for assisting with gripping in order to stabilize the wrist while the wrist/finger flexors are working to hold the object. People with tennis elbow will typically present pain in the lateral elbow with any/all of the following activities:

As previously mentioned, this injury is most commonly a result of overuse and not due to trauma (although I suppose anything is possible....) Think in terms of a grocery clerk scanning items for several hours in a shift, practicing an instrument for several hours, using a computer mouse for long periods of time, etc. People with lateral epicondylitis will commonly have pain with lifting a coffee mug, carrying a bag/briefcase (does anyone actually own briefcases anymore??), playing an instrument, and... dare I say it? Playing tennis.... The good news is that this condition can typically be overcome with the right amount of rest, modification of your activities and guidance from your friendly physical therapist. Make sure that you give your muscles a break and don't abuse them too much. Or, if you do an activity or job that requires you to use these muscles a lot, make sure you treat them to some TLC afterwards.

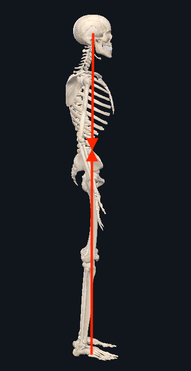

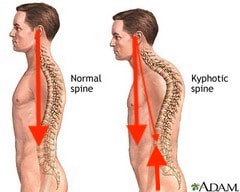

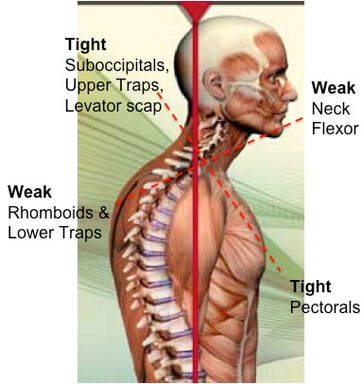

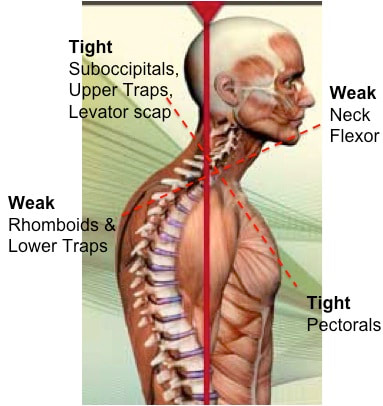

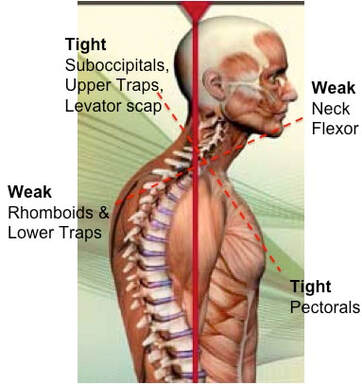

Posture.... That dreaded word that comes up over and over again. Every time people find out that I am a physical therapist, people automatically sit up straight, assuming that I'm going to judge or comment on it. We all have been told time and time again that posture is important, we all think we know what "good posture" is supposed to look like. But, do we really? Over the last four weeks, we've gone on a journey - discussing some key muscle groups that are essential components of posture as it relates to the upper half of your body. We have examined the Rhomboids, Pectoralis Major, Deep Neck Flexors, Suboccipitals and we definitely can't forget the Upper Trapezius (if you want to go back to see what we discussed there, as well as some good ways to keep them happy, go check them out.) For the fifth and final (for now) installment of our posture series, we're going to help tie all of it together into a neat little package (this, in NO way, is EVERYTHING that can be said about posture). In its truest sense, the foundation of posture is the overall alignment of the spine If you look from the side of the body when someone is standing, you will notice that the spine itself is not in a straight column. Instead, it is in a "S" shape. Reason being, is that it is the optimal position in order to allow our body to distribute our weight evenly while still allowing the flexibility and mobility to move freely. When we move out of this normal "S" curve, it results in increased stress on certain portions of the spine in order to keep you upright. Because our skeleton is merely the framework of our body, movements and positions are actually created through tension of our muscles. Two important things to remember as we continue to move forward:

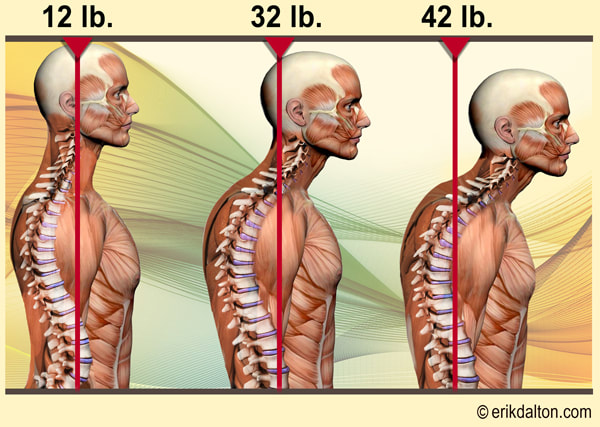

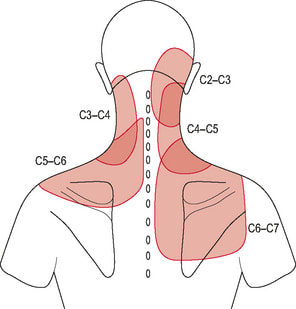

When we talk about posture, we are really talking about the balance and position of the spine, in order to allow our bodies to maintain its position with the LEAST amount of work possible. When we stand with "good alignment", our weight is typically centered around the level of our belly button. In this case, the muscles in the front of our body, in theory, should be working equally as the muscles in the back of our body. If we were to draw a line starting from our ear canal straight down, and another line from the middle of our foot straight up, you would expect the two arrows to meet right in the middle. Today, we're primarily focusing on the upper half of the body. We'll discuss the lower portion another day. Now.... what happens when someone goes into that infamous "slouched posture" (the most common)? If we draw the same line starting from the middle of the head around the ear canal down towards the floor, you will find that the arrows never meet together. Instead, the arrow pointing down from the head will be in front of the one coming up from the ground. What this results in, is the muscles in the back of your neck having to work much harder to keep your head upright (remember the upper trapezius??) Based on biomechanics and physics, for every inch your head moves forward away from the neutral position, it forces the muscles such as the upper trapezius, cervical paraspinals and others to work as if the head were 10 pounds heavier. Think about that for a second...... The average head weighs 12 lbs. Just by shifting your head forward by an inch, the muscles in the back of your neck have to work almost twice as hard to keep your head up instead of looking down at the floor. So when we are in these less-than-ideal postures, not only does it put more pressure on our spine, but it causes certain groups of muscles to work harder. Changing positions or moving for short periods of time is one thing and completely normal. However, given enough time in the same position, your body will adapt so that those muscles become inherently shorter/tighter. So what happens to the other side of the neck? The front? We have talked about the deep neck flexors. Remember those little guys? What happens, is that because the posterior neck muscles are contracted and shortened, the front of the neck gets stretched out. This causes this muscle group to become weaker because the elongated position makes it harder for the muscle to contract and shorten to produce motion If we look at the the chest and upper back, the same imbalance of tight/elongated muscles occurs, but this time the chest muscles (Pectoralis Major/Minor) become tight and the Rhomboids become elongated and weaker. What we haven't talked about (but will in future blog posts) is how the forward head posture not only affects the spinal alignment, but things such as jaw (TMJ) pain as well. There are also consequences of having bad posture in the opposite way, where the spine is almost completely straight (flat back). You want to make sure that you live somewhere right in the middle to keep both sides happy. Having 'lazy' muscles is not the only reason for poor posture. Other reasons include:

Issues that can arise from "poor posture" include:

I want to reiterate that these consequences are primarily when people are in these less-desireable positions for LONG periods of time. In fact, having good balance of muscle activation in other postures is what allows us to be strong and flexible. It's what we're designed to do. So, do not be afraid to move, but be aware of what positions your body is in and make sure that you spend time stretching out if you find yourself in one position for too long.

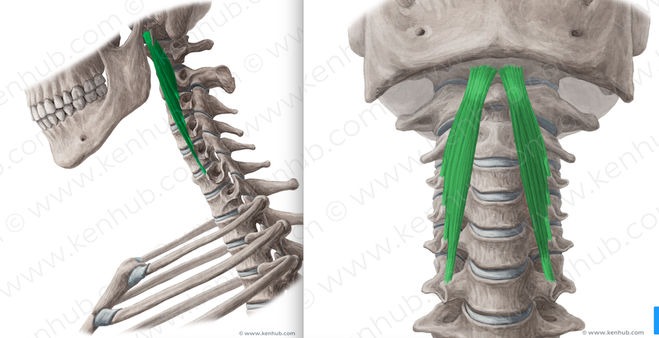

Get up. Move around. Take breaks! That's all for now! Be happy and healthy, and always be asking yourself #whatsyouropus Every time someone talks about 'core strengthening', your mind probably goes straight to "Abs! Abs! Abs!" and "Planks for days!" What if I told you that there is another often-neglected core in your body that is equally as important? Welcome to the fourth installment of our Posture Series. Allow me to introduce the Deep Neck Flexors (DNF) - Longus Colli and Longus Capitis.

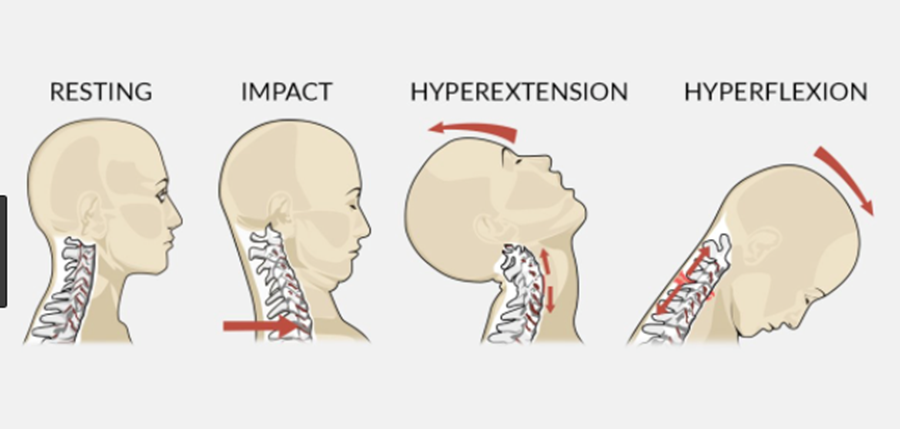

Both of these muscles sit right up against your cervical spine and they work together to flex the spine to a small degree. When working together in a balanced manner in conjunction with the ALL of the muscles around your neck, including our friends the upper trapezius and suboccipitals which we discussed in previous posts, they help stabilize the head and neck through micro adjustments as you move. Neck pain and its effects on muscle activation of these muscles have been widely studied over the last few decades. Studies have found that up to 70% of patients with chronic neck pain actually have decreased muscle activation of the deep neck flexors and sternocleidomastoid (Source). In the same study, subjects with chronic neck pain who underwent a deep neck flexor strengthening program showed significant decreases in overall reported neck pain If you've read my last few blog entries, you are likely now familiar with our poor-postured friend. With poor posture, the DNF complex (the upper/front portion of the cross) gets stretched/elongated which, in turn, results in the muscles becoming inherently weaker and less able to perform the job it was tasked with. This is also significant for people who have experienced whiplash injuries such as being involved in a car crash. In the beginning of the whiplash motion, the head is flung backwards during the hyperextension phase (in the picture below), which strains the anterior neck muscles such as the DNF and sternocleidomastoid muscles (to be discussed in a future post). However on the rebound the head is flung forward, putting increased strain on the upper trapezius/levator scapulae muscles. Depending on the severity and velocity of impact, ligaments supporting the cervical spine may also become sprained. So you have a scenario of what came first? The chicken or the egg? Did neck pain develop which caused the DNF and supporting muscles to become weaker? Or did the DNF get weak because of poor posture, which resulted in neck pain?

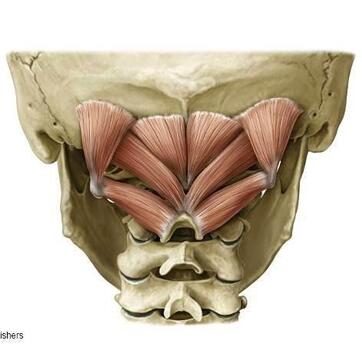

This muscle is particularly important for musicians who are violinists or wind players. With the majority of mankind typically sitting in some kind of slouched posture you can end up relying on those stronger/tighter muscles that we previously discussed (upper trapezius much?) to support the instrument or bring our heads to the instrument to play. Instead, I challenge you to add in a bit of DNF strengthening into your warmup routine. Next week will be our final installment of the Posture series, where we spend a little more time with our poor postured friend and link some of these muscles together. While they are not the ONLY ones affected by posture, it's important to start to think about how they all affect each other and give you a better understanding of how they work. Until next time, Stay happy and healthy! This week's Muscle Monday is dedicated to the little group of muscles that often speak to us in times of stress. While there are MANY causes and types of headaches, it is estimated that 50% of all adults will experience a headache in the last year (Source: World Health Organization). Tension-Type headaches are the most common form of headaches, which can either be due to muscle tension as a result of stress or other musculoskeletal problems coming from the neck. With that being said, allow me to introduce our Fantastic Four, The Suboccipitals:

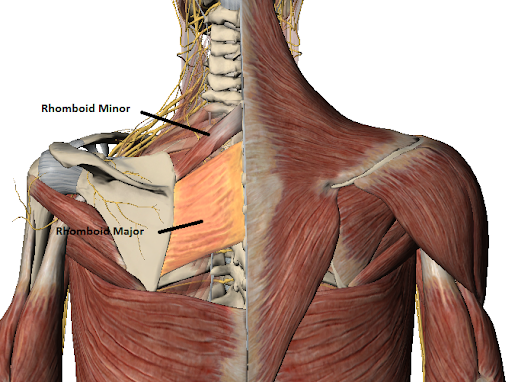

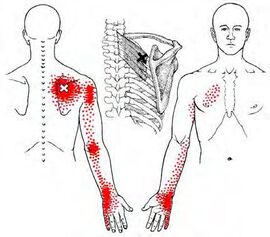

[Muscle Monday] Nagging Shoulder Blade Pain Got You Down? - Consider the Rhomboid Major and Minor5/24/2020 Have you ever wondered why you may be getting pain between your shoulder blade and spine? For the second installment of our posture series, we will be discussing the Rhomboid Major and Minor. While they are two muscles, they almost always work together. Over the next few posts, we will be exploring some of the major muscles related to posture and how they work together. If you'd like to read our previous posts about posture, click here. Let's get things started. Allow me to present to you the Rhomboid Major and Minor: This dynamic duo attaches to from the spinous process of the last cervical segment (C7) and upper thoracic spine (T1-5) to the medial border of the shoulder blade. It sits one layer underneath the trapezius muscle, which we discussed in a previous post. The rhomboid minor is located superior/above the larger, broader rhomboid major muscle. Both work together to pull the shoulder blade towards the spine, otherwise known as "scapular retraction." Image source: Complete Anatomy This muscle is essential to the stability of the whole shoulder complex as it works to keep the shoulder blade supported during arm movements in all directions. The rhomboids can be a common source of pain in the area between the spine and your shoulder blade. Often times people will report pain, dull, aching or occasionally sharp pain to that region. This pain is very common in people who do a lot of prolonged work at a computer (particularly in the mousing hand), as well as musicians who have to hold their instruments in one position for long durations (flutists, violinists) One thing that should be acknowledged is that people can feel pain in other areas aside from the actual tissue source. The picture below demonstrates some common referral patterns where people may experience symptoms when there is a trigger point on the rhomboid ('X' marks the spot). It is imperative that I warn you that 'trigger points' are not the only source of pain that can refer in this location or pattern. For example, there are joint-related pain that can also refer pain to similar areas. One of the most common ways that cues clinicians like me to suspect muscle-related/trigger point pain (other than palpating the muscle) is if patients often describe the pain as coming on after a prolonged period of time and they have to fidget around or change positions frequently to find a more comfortable posture. If you are unsure, be sure to seek out help from your friendly Physical Therapist (including us) to help you navigate this issue and help steer you back onto the right path. We will discuss trigger points and what they actually are in an upcoming post. When looking at overall posture, these muscles are significant because when in a slouched posture, these muscles are commonly in a stretched position. This makes it more difficult for them to generate the amount of force needed to help hold the scapula in place. Remember this image? The harder these muscles have to work, the less time it takes for them to start to fatigue, which can be interpreted by your brain as that dull, aching sensation that you may feel.

The best way to avoid this fatigue is to make sure that you have enough flexibility in the opposing muscles, such as the pectorals and the upper trapezius, and enough strength in the supporting muscles. Check out our post on Instagram for some ideas of some simple exercises you can do to get things moving in the right direction. Can't wait to share more about posture next week Until next time, stay happy and healthy! The next few episodes of Muscle Monday will be dedicated to discussing important muscles related to Posture. Questions about posture are probably one of the top things people ask me about on a regular basis, and the answer is not as simple as it seems. Posture involves many components which need to work together just-so in order to create the ideal scenario for your body to function at its best. Today, we will be talking about the might Pectoralis Major. To say that this muscle is important would be redundant, because (almost) ALL muscles have a specific function, but this one in particular often gets a bad rep because it is associated with poor posture. In reality, it is an extremely versatile muscle that is used in most shoulder movements. Let's explore some fun facts about this muscle Fact #2: The pec major can affect both the glenohumeral (shoulder) joint and the the scapula Due to its attachment on the clavicle, when the two portions of the pec major work together, they can depress the shoulder girdle Fact #3: The pec major performs movements in 5 planes of shoulder motion Because the muscle has two portions, the orientation of the muscle fibers allow it to move your shoulder in several planes of motion. The clavicular fibers assist with shoulder flexion while the sternal fibers assist with shoulder abduction AND extension. When the two portions work together, they will perform shoulder horizontal adduction, as well as shoulder (glenohumeral joint) internal rotation. Fact #4: Constantly sitting in a "slouched posture" will result in your pec major to get tight

Fact #5: In order to adequately take care of your body, you must do a combination of strengthening and stretching. It's all about balance. First of all, try and think about what positions you are in the most frequently and take the time to stretch in the opposite directions, no matter what that may be. Because most of us these days spend a lot of time sitting in front of a computer, on the couch or looking at our phones (or a combination of all 3?), you must make an effort to make sure that the muscle doesn't get too tight. Conversely, if you perform a task that requires a lot of pec use - such as playing a bowed instrument (Right arm), playing tennis, etc., you may want to invest a portion of your exercise routine to working on building strength, as it is also a key player in your overall shoulder stability. Take some time and check out this stretch to help improve your shoulder's powerhouse. Next week, we will be discussing the Pec Major's little brother, the Pec Minor. You're not going to want to miss it.

Until next time, stay happy and healthy! If you've been finding yourself sitting on the couch or at the computer for hours on end, this post is for you. So remember last post when I spoke about muscles seldom work in insolation? The same goes true for this week's featured muscle, but we'll just bring it back in and focus on our friend: The Transverse Abdominis I grew up playing tennis and practicing Tae Kwon Do. Later on in college, I rowed (much to my piano teacher's dismay --- my hands were ALWAYS blistered and torn up). What is the one thing during the workouts that ALL of my coaches (but none of my music professors) talked about? "You must strengthen the core"

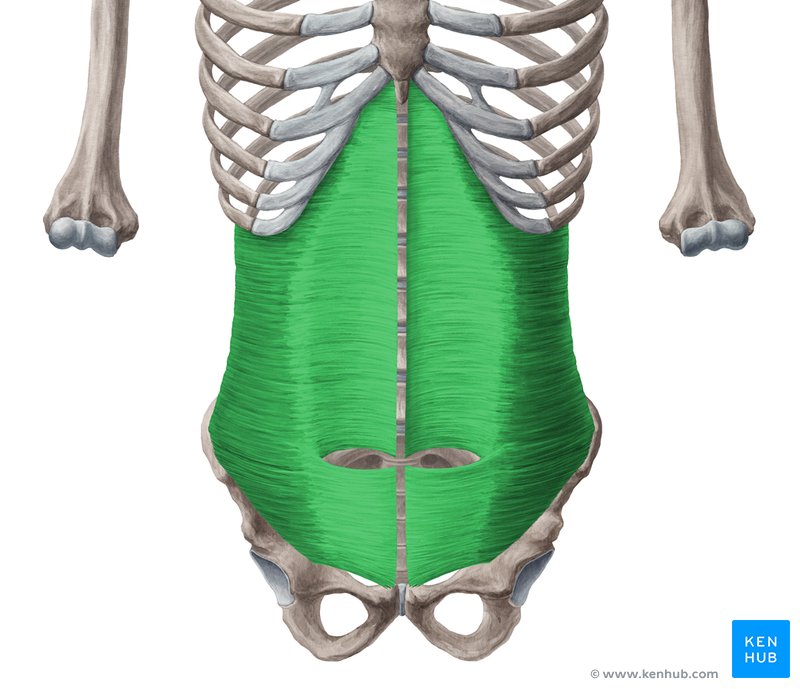

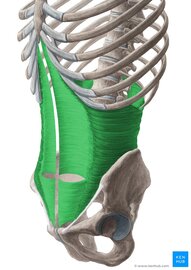

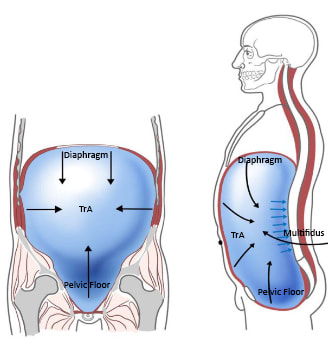

The Transverse Abdominis (TrA) is one component of the system of muscles that make up your core (stay tuned for further discussions regarding the core) The muscle is extremely broad - stretching across your torso. It attaches on the lower 6 ribs from the top, into the pubic bone on your pelvis. Medially, it attaches right down the middle of your abdomen via a facial junction and wraps around the sides and attaches into the fascia connecting to your abdominal obliques (internus). Image Credit: Kenhub.com If you take a look at any of the other muscle pictures that I have posted, or even ones you can find online, understand that muscles will pull parallel to the orientations of its fibers. So in this particular case, they draw your stomach inwards like this: It's not so much of a "sucking in your belly" type of motion, which is a common misconception. This is a 3D motion that occurs around your torso. Simplest way - if you've ever worn or seen a corset like they used to wear way back when, it's that kind of cinching together motion that this muscle performs. Now, why is this significant? As the TrA contracts, it works in conjunction with other muscles in the back, pelvic floor in order to increase the pressure inside the abdominal cavity. That pressure will then push up against the lumbar spine to add even more stability. Whether you're walking, standing up from a chair, or raising your arm to retrieve an object, this core stability is essential in all aspects of human movement. In fact, it is so essential, that even as you reach out your arm to pick something up, your body anticipates the task and activates this system before it even happens. This means that your body should automatically engage all of the muscles before you even consciously realize that you're going to do it.

But wait.... There's more..... Many studies including this one and this O.G. study found that in subjects with low back pain, there was a delay in core muscle recruitment. We're not talking seconds or minutes, but even a millisecond delay can result in decreased core stability with performing a task (like a conductor starting his downbeat when no one is prepared) which ultimately can exacerbate the problem further, due to the lack of initial stabilization. This is a type of muscle that needs endurance training more-so than brute strength. So as you're going about your daily routine or workouts, see if you can feel your core kick on. Planks are a great place to start, but so are most fully body exercises because remember - you are never working out alone. Until next time, stay happy and healthy! |

AuthorDr. Janice Ying is a Los Angeles-based Physical Therapist. She is board-certified Orthopedic Physical Therapy Specialist and is regarded as a leading expert in the field of Performing Arts Medicine and the development of cutting edge injury prevention and rehabilitation programs for musicians. DisclaimerThe information on this website is intended for educational purposes and should NOT be construed as medical advice. If you have or think you have a health-related issue which needs to be addressed, please seek the help from your local licensed medical professional.

Archives

October 2020

Categories

All

|

We would love to see you soon!

|

© Opus Physical Therapy and Performance - 2021 - All Rights Reserved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed